As a result of the damaged joint surface and/or the fractured fragments present in the joint space, there is pain and inflammation and the movement at the joint becomes painful and restricted.

Moreover, injury to the bone may damage its blood supply, leading to aseptic necrosis of the bone (death of bone cells in the absence of an infection). The overlying cartilage derives its nutrition from the fluid in the joint space and therefore does not suffer from a lack of blood flow.

Aseptic necrosis is a major factor impeding the healing of talar dome fractures.

Symptoms:

A great number of talar dome fractures usually occur with an ankle sprain, a result of an accidental inward twist of the foot.

Along with the pain of damaged ligaments, there is a deep-set pain in the ankle, which persists for longer, even after the initial intense pain has subsided.

Return to activity leads to recurrent pain and swelling.

There may be stiffness of the joint (a locking sensation during movement) and crepitance (a grating or crackling sound on movement).

There may be weakness and instability of the joint.

Diagnosis:

Talar dome fractures are often missed at the initial examination following an ankle sprain or injury.

The treatment given for the sprain or injury usually fails to treat the unidentified fracture. The result is a persistent deep pain in the ankle and recurrent swelling with activity.

Follow-up X-rays, about 4 to 6 weeks after injury, should be taken to rule out any fractures of the talar dome.

Moreover, in the case of fracture of the outer side of the talar dome there is tenderness in front of the outer bump of the ankle with the foot bent downwards.

However, if there is tenderness behind the inner bump of the ankle with the foot bent upwards, the inner side of the talar dome is involved.

If initial X-rays do not show any evidence of fracture despite the signs and symptoms, a bone scan, CT scan or MRI may be advised. These diagnostic tools are especially helpful in diagnosing Stage I osteochondral defects and in assessing the extent of the damage to the bone.

Treatment:

Conservative Treatment:

The treatment of a talar dome fracture is often delayed due to late diagnosis. However, it is recommended to initiate the treatment with a conservative approach, which includes:

- Rest

- Immobilizing the joint using an ankle brace or walking cast for about six to ten weeks

- Using crutches to keep the load off the fractured bone

- Pain killers

Non-displaced fractures of the talar dome usually heal with this treatment approach. However, even if conservative treatment fails to resolve the problem, it does not complicate the problem any further nor does it cause any problem if an operation is planned afterwards.

Surgery is required for:

- Healed fractures leaving a defect on the cartilage covering the joint surface of the bone; this causes pain and instability of the joint

- Displaced fractures (fractured fragments dislocated into the joint space)

Once the immobilizing cast is removed, the condition of the bone should be re-evaluated. If there are any symptoms of joint dysfunction such as:

- A locking of the ankle joint

- Instability of the joint

- Pain in the joint (that goes away with injecting a local anesthetic)

An MRI or other diagnostic tools should be employed to check for the displaced fractured fragments and for any residual defects in the cartilage covering the joint surface of the bone.

Surgical treatment involves:

Arthroscopy (repairing the damaged bone with the help of an arthroscope):

This involves making a small incision through which an arthroscope (a small tube with an optical system to look into the joint, attached to a monitor or TV screen) is inserted to clean the surface of damaged cartilage by grinding away the defect. In some cases, this arthroscopic procedure is accompanied by drilling the bone under the cartilage to stimulate blood flow to the area and speed up healing and to prevent aseptic necrosis of the bone.

Internal fixation using pins and screws

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation:

This involves opening up the skin for reduction (fixation or correction of a fracture) with the help of internal fixation (joining fractured fragments of bone using pins and screws placed inside the bone).

This requires a relatively larger skin incision than is used in arthroscopy and may involve the placement of a graft to rectify the shape of the damaged talar dome.

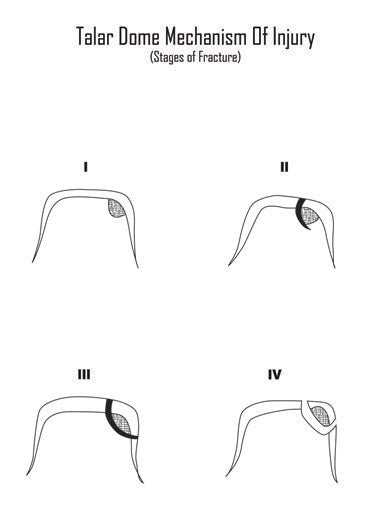

Stage I and II fractures usually require arthroscopy with or without drilling of the underlying bone

Stage III and IV fractures do respond to the arthroscopic approach, but often require open surgery and graft placement.

After complete healing of the fracture, proper rehabilitation is required to improve the strength and stability of the joint as well as its range of motion.